BACKGROUND:

This project’s naissance was in the bottom shelves of a local history & genealogy department of a middling public library in Maine. Resting on those shelves are cemetery maps, names and dates—data one could employ to find the resting place of an ancestor, or fodder for any number of studies and stories—cloistered in binders, on paper.

It continued to develop as I looked for electronic sources to populate the data model I was developing. While recent years have seen genealogical records become increasingly available and connected, the same cannot be said for the myriad, disparate sites that house cemetery records. My wish was to find a way to make all of this data available, sharable, and reusable. I would like it to be able to ingest digital information, as I have done with data harvested from BillionGraves.com, but also allow for manual entry for the analog records.

Ultimately the JSON-LD model best met both needs—it is human and machine readable, and the @context keyword transforms static data into semantic information that can be queried and reused.

PROCESS:

To say this developed in fits and starts is an understatement. While the overarching plan was clear to me, it was difficult to find the proper starting place. Cemetery data is housed in many silos, all with different structures and strategies. I began by querying the BillionGraves API, and while I was able to pull data from some other sites, the data from BillionGraves was the best structured (JSON) and cleanest (relatively speaking). That is the initial obstacle to creating a unified collection of cemetery data—that no two current repositories have the same methods of access, so each require unique scripts to harvest and format data.

I chose to focus on Maine for a couple reasons beyond my general obsession with the state. For one, BillionGraves makes it easy to search all cemeteries by state, and given Maine’s size, that provided a reasonable dataset—not too unwieldy, but with plenty to start with. Also, my familiarity with the state and its localities allowed me to recognize discrepancies and idiosyncrasies that otherwise would have gone unnoticed—in all, I felt most comfortable with the data, which helped inform my approaches. This process could very easily be replicated for all 50 states (and many other countries!) with minimal tweaks to the scripts.

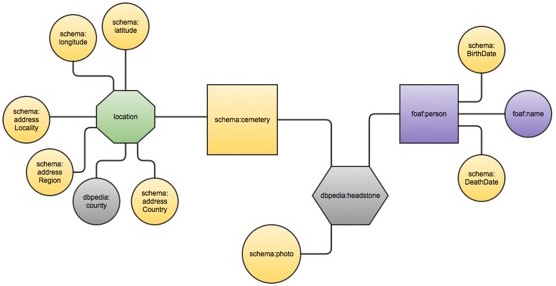

In addition to the issue of structure variance between sites, the available fields were variable as well. I struggled with where to draw the line concerning granularity. Ultimately I would like to include more terms, indicating military service, for example, or referencing others interred in the same plot (for relationship mapping purposes). This first iteration of JSON-LD context is minimal, defining name, birth and death date, and cemetery along with location (latitude and longitude, as well as the named place). I settled with that for now, as that is really all the information one would require to find a grave, which is the most basic purpose of the project. Adding more fields would accomplish my grander goals by disambiguating between like-named individuals, for example, and generally providing fodder for historical population studies.

SCHEMA VISUALIZATION:

Colors indicate namespace used.

SCRIPTS & DATA FILES:

There are two scripts necessary, one to retrieve the data (BG_indiv_params.py) and the second (map_data_to_schema.py) to map the values to the terms specified in the context file (CemeterySchema_JSONLD.json).

I provided the data files, including the initial query of all the cemeteries in the state, which was obtained by using a simple script (BG_state_cem.py) to produce all the cemetery identifiers, which were in turn put into a list for use in the data-harvesting script. I selected only cemeteries with five or more records.

I ran my BG_indiv_params script with the complete list of populated cemeteries, the result can be found in people_data_n100.json. I set the limit to 100 individual records/cemetery simply so it wouldn’t take forever to run. There was an incredible amount of variation in the number of records/cemetery, from 0 to 1700, so the data I produced is a representative, not exhaustive, list. Finally, I ran the data through the map_data_to_schema script, which resulted in 12.10.2014records_n100.json.