For my project, I used the Victoria & Albert Museum’s API (http://www.vam.ac.uk/api/). I found the API to be more usable than other museum APIs because it offers a Query Builder, which allowed me to build a URL; the Builder made it clear which parameters I needed to use when writing my script.

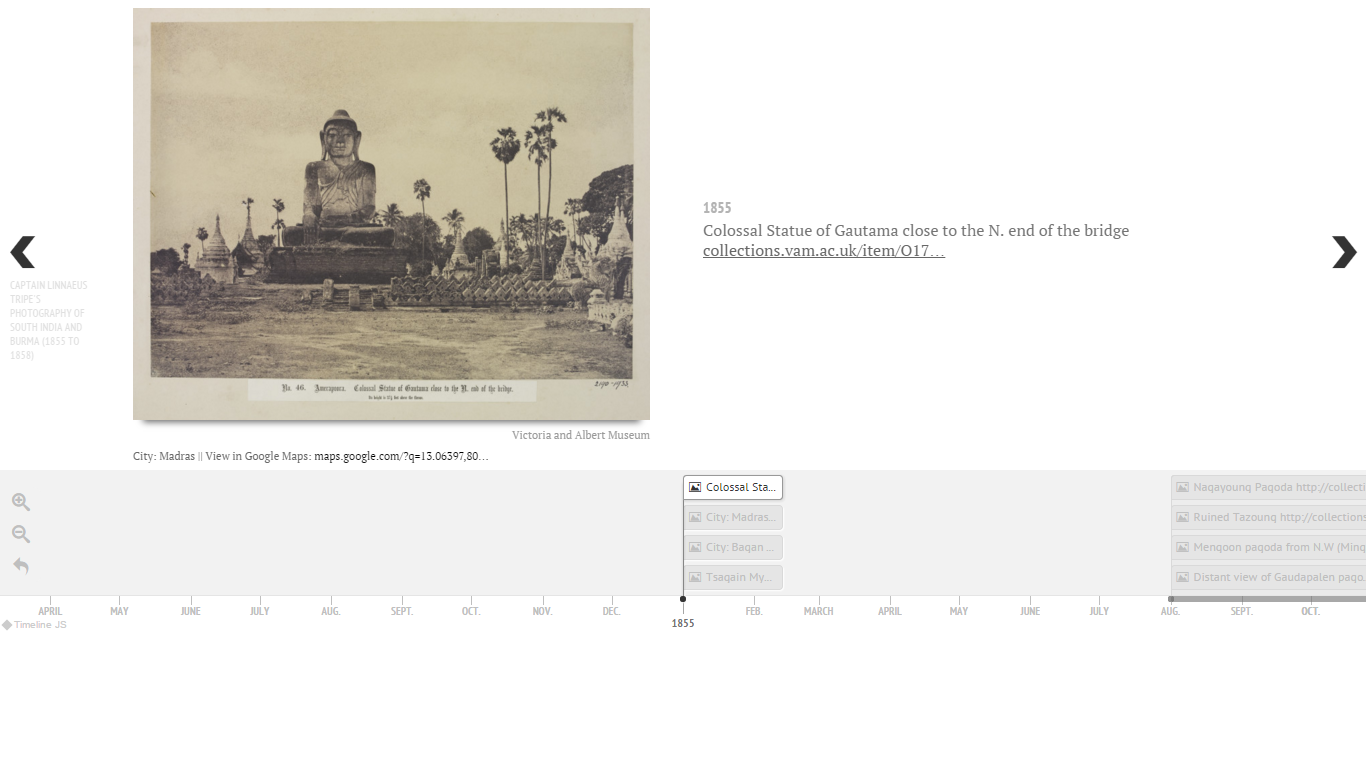

I chose to work with the V&A’s collection of Linnaeus Tripe’s photography of South India and Burma (Myanmar) because it offered latitude and longitude metadata, and my plan was to visually map where each photograph was taken. Unfortunately, after mapping my data in CartoDB, the photographs were concentrated in only a few areas and weren’t visually appealing.

The first coding difficulty I had was determining how to view all records. After experimenting with the range function, I found that I needed to start at 0, stop at 129 (total records), and “step” in increments of 45 (the maximum amount of records that the V&A museum allows to be viewed at once). After defining the range function, I kept getting inaccurate results when I first ran the script; I wasn’t getting the 129 photograph records I knew existed in return. I then realized “'images' : 1” needed to be added as a parameter in order to indicate I was only interested in images. The most difficulty I had was writing my results to a .csv file. Once the script finally wrote to the csv, the columns were a mess, there wasn’t much spacing. Using “row = [str(x).replace("\n", "") for x in row” allowed for spaces.

For my visualization, I chose to work with Northwestern University Knight Lab's Timeline JS, a tool for creating interactive timelines. It is a usable program; you download a template and add your data into the template’s columns accordingly. The data needs to be structured properly to Timeline JS’s constraints or else it will not be viewable. I wanted to use the Wikipedia API in order pull URLs of websites pertaining to the monuments and locations mentioned in the V&A’s description of each photograph (though, some photographs are missing cataloged descriptions)--however, many of the described monuments do not have Wikipedia pages, so I had to manually search for each description in the V&A’s catalog and add the links to my Timeline.

Lastly, since it was my main reason for choosing the Tripe collection, I wanted to incorporate latitude and longitude somehow. I concatenated the latitude and longitude and a standard Google Maps URL to come up with a direct link to that latitude and longitude in Google Maps. It seems that the given latitudes and longitudes are only for the city, not the exact location of where the photograph was taken. Regardless, it is interesting to view the setting of the mid-19th century photograph in a modern context. Sadly, one can’t quite see these incredibly constructed monuments and architecture in Google Maps today.